All about art, artists and much more!

ART MOVEMENTS :

MINIMALISM

In visual arts, music, and other mediums, minimalism is an art movement that began in post–World War II Western art, most strongly with American visual arts in the 1960s and early 1970s. Prominent artists associated with minimalism include Donald Judd, Agnes Martin, Dan Flavin, Carl Andre, Robert Morris, Anne Truitt, and Frank Stella.

The movement is often interpreted as a reaction against abstract expressionism and modernism; it anticipated contemporary post minimal art practices, which extend or reflect on minimalism’s original objectives.

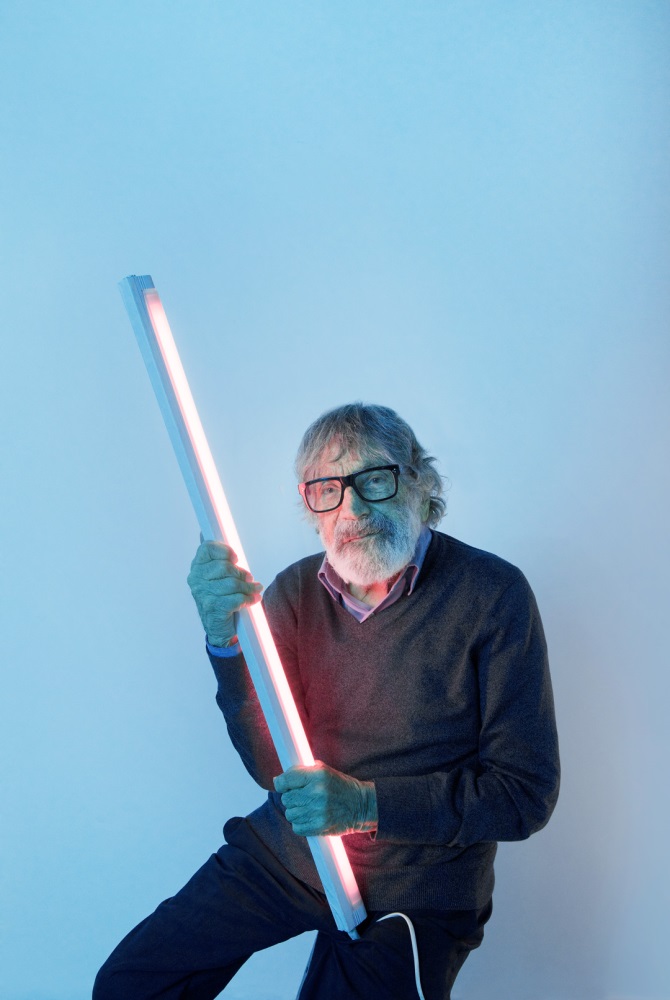

Minimalism in visual art, generally referred to as “minimal art”, “literalist art” and “ABC Art” emerged in New York in the early 1960s as new and older artists moved toward geometric abstraction; exploring via painting in the cases of Frank Stella, Kenneth Noland, Al Held, Ellsworth Kelly, Robert Ryman and others; and sculpture in the works of various artists including David Smith, Anthony Caro, Tony Smith, Sol LeWitt, Carl Andre, Dan Flavin, Donald Judd and others. Judd’s sculpture was showcased in 1964 at Green Gallery in Manhattan, as were Flavin’s first fluorescent light works, while other leading Manhattan galleries like Leo Castelli Gallery and Pace Gallery also began to showcase artists focused on geometric abstraction. In addition there were two seminal and influential museum exhibitions: Primary Structures: Younger American and British Sculpture shown from April 27 – June 12, 1966 at the Jewish Museum in New York, organized by the museum’s Curator of Painting and Sculpture, Kynaston McShine and Systemic Painting, at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum curated by Lawrence Alloway also in 1966 that showcased Geometric abstraction in the American art world via Shaped canvas, Color Field, and Hard-edge painting. In the wake of those exhibitions and a few others the art movement called minimal art emerged.

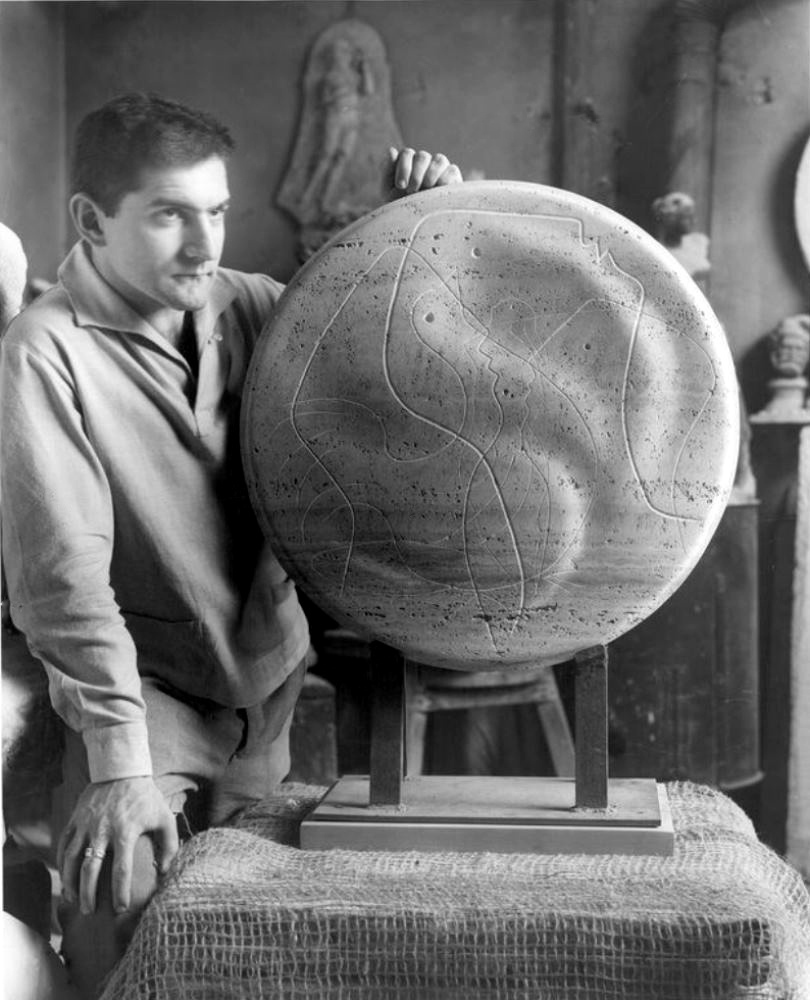

In a more broad and general sense, one finds European roots of minimalism in the geometric abstractions of painters associated with the Bauhaus, in the works of Kazimir Malevich, Piet Mondrian and other artists associated with the De Stijl movement, and the Russian Constructivist movement, and in the work of the Romanian sculptor Constantin Brâncuși.

In France between 1947 and 1948, Yves Klein conceived his Monotone Symphony (1949, formally The Monotone-Silence Symphony) that consisted of a single 20-minute sustained chord followed by a 20-minute silence – a precedent to both La Monte Young’s drone music and John Cage’s 4′33″. Klein had painted monochromes as early as 1949, and held the first private exhibition of this work in 1950—but his first public showing was the publication of the Artist’s book Yves: Peintures in November 1954.

Minimal art is also inspired in part by the paintings of Barnett Newman, Ad Reinhardt, Josef Albers, and the works of artists as diverse as Pablo Picasso, Marcel Duchamp, Giorgio Morandi, and others. Minimalism was also a reaction against the painterly subjectivity of Abstract Expressionism that had been dominant in the New York School during the 1940s and 1950s.

Artist and critic Thomas Lawson noted in his 1981 Artforum essay Last Exit: Painting, minimalism did not reject Clement Greenberg’s claims about modernist painting’s reduction to surface and materials so much as take his claims literally. According to Lawson, minimalism was the result, even though the term “minimalism” was not generally embraced by the artists associated with it, and many practitioners of art designated minimalist by critics did not identify it as a movement as such.

Also taking exception to this claim was Clement Greenberg himself; in his 1978 postscript to his essay Modernist Painting he disavowed this interpretation of what he said, writing:

There have been some further constructions of what I wrote that go over into preposterousness:

I regard flatness and the inclosing of flatness not just as the limiting conditions of pictorial art, but as criteria of aesthetic quality in pictorial art; that the further a work advances the self-definition of an art, the better that work is bound to be. The philosopher or art historian who can envision me—or anyone at all—arriving at aesthetic judgments in this way reads shockingly more into himself or herself than into my article.

In contrast to the previous decade’s more subjective Abstract Expressionists, with the exceptions of Barnett Newman and Ad Reinhardt; minimalists were also influenced by composers John Cage and LaMonte Young, poet William Carlos Williams, and the landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted. They very explicitly stated that their art was not about self-expression, and unlike the previous decade’s more subjective philosophy about art making theirs was ‘objective’. In general, minimalism’s features included geometric, often cubic forms purged of much metaphor, equality of parts, repetition, neutral surfaces, and industrial materials.

Robert Morris, a theorist and artist, wrote a three part essay, “Notes on Sculpture 1–3”, originally published across three issues of Artforum in 1966. In these essays, Morris attempted to define a conceptual framework and formal elements for himself and one that would embrace the practices of his contemporaries. These essays paid great attention to the idea of the gestalt – “parts… bound together in such a way that they create a maximum resistance to perceptual separation.” Morris later described an art represented by a “marked lateral spread and no regularized units or symmetrical intervals…” in “Notes on Sculpture 4: Beyond Objects”, originally published in Artforum, 1969, continuing on to say that “indeterminacy of arrangement of parts is a literal aspect of the physical existence of the thing.” The general shift in theory of which this essay is an expression suggests the transition into what would later be referred to as post minimalism.

One of the first artists specifically associated with minimalism was the painter Frank Stella, four of whose early “black paintings” were included in the 1959 show, 16 Americans, organized by Dorothy Miller at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. The width of the stripes in Frank Stellas’s black paintings were often determined by the dimensions of the lumber he used for stretchers to support the canvas, visible against the canvas as the depth of the painting when viewed from the side. Stella’s decisions about structures on the front surface of the canvas were therefore not entirely subjective, but pre-conditioned by a “given” feature of the physical construction of the support. In the show catalog, Carl Andre noted, “Art excludes the unnecessary. Frank Stella has found it necessary to paint stripes. There is nothing else in his painting.” These reductive works were in sharp contrast to the energy-filled and apparently highly subjective and emotionally charged paintings of Willem de Kooning or Franz Kline and, in terms of precedent among the previous generation of abstract expressionists, leaned more toward the less gestural, often somber, color field paintings of Barnett Newman and Mark Rothko. Stella received immediate attention from the MoMA show, but other artists—including Kenneth Noland, Gene Davis, Robert Motherwell, and Robert Ryman—had also begun to explore stripes, monochromatic and Hard-edge formats from the late 50s through the 1960s.

Because of a tendency in minimal art to exclude the pictorial, illusionistic and fictive in favor of the literal, there was a movement away from painterly and toward sculptural concerns. Donald Judd had started as a painter, and ended as a creator of objects. His seminal essay, “Specific Objects” (published in Arts Yearbook 8, 1965), was a touchstone of theory for the formation of minimalist aesthetics. In this essay, Judd found a starting point for a new territory for American art, and a simultaneous rejection of residual inherited European artistic values. He pointed to evidence of this development in the works of an array of artists active in New York at the time, including Jasper Johns, Dan Flavin and Lee Bontecou. Of “preliminary” importance for Judd was the work of George Earl Ortman, who had concretized and distilled painting’s forms into blunt, tough, philosophically charged geometries. These Specific Objects inhabited a space not then comfortably classifiable as either painting or sculpture. That the categorical identity of such objects was itself in question, and that they avoided easy association with well-worn and over-familiar conventions, was a part of their value for Judd.

This movement was criticized by modernist formalist art critics and historians. Some critics thought minimal art represented a misunderstanding of the modern dialectic of painting and sculpture as defined by critic Clement Greenberg, arguably the dominant American critic of painting in the period leading up to the 1960s. The most notable critique of minimalism was produced by Michael Fried, a formalist critic, who objected to the work on the basis of its “theatricality”. In Art and Objecthood (published in Artforum in June 1967) he declared that the minimal work of art, particularly minimal sculpture, was based on an engagement with the physicality of the spectator. He argued that work like Robert Morris’s transformed the act of viewing into a type of spectacle, in which the artifice of the act observation and the viewer’s participation in the work were unveiled. Fried saw this displacement of the viewer’s experience from an aesthetic engagement within, to an event outside of the artwork as a failure of minimal art. Fried’s essay was immediately challenged by postminimalist and earth artist Robert Smithson in a letter to the editor in the October issue of Artforum. Smithson stated the following: “What Fried fears most is the consciousness of what he is doing—namely being himself theatrical.”

In addition to the already mentioned Robert Morris, Frank Stella, Carl Andre, Robert Ryman and Donald Judd other minimal artists include: Robert Mangold, Larry Bell, Dan Flavin, Sol LeWitt, Charles Hinman, Ronald Bladen, Paul Mogensen, Ronald Davis, David Novros, Brice Marden, Blinky Palermo, Agnes Martin, Jo Baer, John McCracken, Ad Reinhardt, Fred Sandback, Richard Serra, Tony Smith, Patricia Johanson, and Anne Truitt.

Ad Reinhardt, actually an artist of the Abstract Expressionist generation, but one whose reductive nearly all-black paintings seemed to anticipate minimalism, had this to say about the value of a reductive approach to art:

The more stuff in it, the busier the work of art, the worse it is. More is less. Less is more. The eye is a menace to clear sight. The laying bare of oneself is obscene. Art begins with the getting rid of nature.

Reinhardt’s remark directly addresses and contradicts Hans Hofmann’s regard for nature as the source of his own abstract expressionist paintings.

In a famous exchange between Hofmann and Jackson Pollock as told by Lee Krasner in an interview with Dorothy Strickler in 1964; for the Smithsonian Institution Archives of American Art.

In Krasner’s words:

When I brought Hofmann up to meet Pollock and see his work which was before we moved here, Hofmann’s reaction was—one of the questions he asked Jackson was, “Do you work from nature?” There were no still lifes around or models around and Jackson’s answer was, “I am nature.” And Hofmann’s reply was, “Ah, but if you work by heart, you will repeat yourself.” To which Jackson did not reply at all.

The meeting between Pollock and Hofmann took place in 1942.

THE ZERO MOVEMENT

In the 1950s the German artist group ZERO wanted to establish a new concept of art. They proclaimed the zero hour for German post-war art and became, in barely a decade, one of the most important avant-garde movements of the twentieth century.

In retrospect, we must call epochal that 11 April 1957 when two young Düsseldorf artists invited the public into their studio and there proclaimed the zero hour of post-war art. It was birth of ZERO. A series of evening exhibitions, at the “Ruins Studio” in the Gladbacher Straße 69, Düsseldorf, by Otto Piene, Heinz Mack and a little later Günther Uecker marked the beginning of a new avant-garde. In this time of upheaval the name ZERO designated both a new artistic and historical beginning, an emancipation from traditional genres and traditional principles of art.

The new beginning announced by the group rested on the ideal of “pure light”. Heinz Mack and Otto Piene saw themselves as an artistic movement inspired by the spirit of change and representing as a new foundation “that should serve as ground zero and starting-point for a fresh awareness of our surroundings”. They developed a new visual and formal language: light and movement moved to the centre of their artistic work, they reduced everything figurative. Their quest has been directed ever since to a purist concentration on the clarity of pure colour and the dynamic vibration of light in space. “Kinetic light art” is the magic word that materialises in the form of discs of light, spheres of light, whole rooms of light. Otto Piene’s Lichtballett (Light Ballet) is one of the major works of the movement. Using the parameters of light, structure, vibration and monochromy, ZERO ventured from the start daring, creative experiments, accompanied by spectacular and now legendary actions and environments.

The avant-garde group dissolved itself as spectacularly as it had kindled its ideas: with a party, where they set rolling a flaming wagon in the direction of the Rhine and let it sink hissing beneath the waves. Of the party, Mack wrote: “In 1966 ZERO found a positive end. Over a thousand people celebrated it one night. I had myself desired this end: an end that I found quite as liberating as had been the beginning of ZERO”.