Frans Masereel was born 31st of July 1889 and died on January, 3 in 1972. He was a Flemish painter and graphic artist who worked mainly in France, known especially for his woodcuts focused on political and social issues, such as war and capitalism.

He mainly worked between Switzerland, Germany and France. Committed artist, humanist, libertarian, anti-militarist pacifist, marked by the bloody torment of the First World War, his works uncompromisingly denounce the horrors of war, oppression and social injustice.

Masereel’s woodcuts influenced Lynd Ward and later graphic artists such as Clifford Harper, Eric Drooker, George Walker, New Yorker cartoonist Peter Arno and Otto Nückel.

Author of a profuse work, tireless illustrator and teacher, his most famous graphic work is undoubtedly: Mon livre d’heures (My book of hours) of 1919: it is considered as such as the precursor of the graphic novel.

He completed over 40 textless novels or novel without words in his career, and among these, his greatest is generally said to be Passionate Journey.

Frans Masereel was born in the Belgian coastal town Blankenberge on 31 July 1889, son of François Masereel and Louise Vandekerckhove a bourgeois couple. In 1894, the Masereel family moved to Ghent where François Masereel died in November. Frans’ mother remarried in 1897 to Louis Lava, a liberal Flemish francophone and free-thinker he undoubtedly had a decisive influence on the young Frans, who’s lost his father at the age of five.

The physician with strong Socialist convictions, and the family together regularly protested against the appalling working conditions of the Ghent textile workers.

After middle school, Frans Masereel spent a year at the Athénée Royale in Ghent, where he primarily practiced drawing. Then he enrolled in 1906 at the Stedelijke Ambachtsschool voor Jongelingen in Ghent, a sort of vocational school teaching arts and crafts. He was introduced to lithography and typography and stayed there for three years. From October 1907 to October 1910, he also followed evening classes at the Academy of Fine Arts in Ghent in the class of Jean Delvin.

In 1909, exempt from military service, he made a first trip to Paris and went to England and Germany. In 1910, he went to Tunisia with his future wife Pauline Imhoff (1878-1968) and moved with her and her daughter to Paris at the end of 1911. There he met the anarchist Henri Guilbeaux who introduced him to great writers such as Stefan Zweig with whom he binds strong bonds of friendship. In 1912 and 1913, he participated in the Salon des Indépendants and met with some success. This first Parisian period allowed him to become familiar with wood engraving through readings on anonymous 15th century engravers, the imagery of Épinal, old playing cards, Dürer, the incunabula and the biblia pauperum of the early Middle-Ages.

In August 1914, while in Brittany, Frans Masereel was surprised by the declaration of war and quickly went to Ghent where he discovered that he had been deleted from the population registers. His military obligations not being clearly defined, he returned to Paris at the end of October. He did not return to Belgium until fifteen years later and did not see his parents for six years. The horrors of war mark his pacifist and humanist commitment and he will never stop denouncing violence and the mechanics of conflicts through his graphic work. He participated in the collection of drawings The Great War and illustrated the novel by Belgian journalist Roland de Marès (1874-1955), La Belgique invadie (Paris, Georges Crès, 1915), with sketches taken from life: this is his first work as an illustrator.

During 1915, after obtaining a visa, he joined the pacifist and conscientious objector Henri Guilbeaux in Geneva, Switzerland, where he remained until 1921. He worked as a volunteer translator for the International Committee of the Red Cross and got to know French writer Romain Rolland. This learned man, resolutely pacifist, becomes the mastermind of Masereel, then 26 years old. In addition to his activity as a translator, he worked as an illustrator for pacifist newspapers and magazines such as Demain de Guilbeaux, Tablettes de Claude Le Maguet (pseudonym of the anarcho-syndicalist Jean Salives) and, from August 28, 1917, La Feuille, where he is an essential collaborator.

It was in 1917 that he published his first two series of woodcuts ‘’the dead standing’’ and ‘’the dead speak’’ (Debout les morts & Les morts parlent). This Swiss period is decisive in the artist’s life: it is the real starting point of his work. He was exhibited at the Tanner Gallery in Zurich in 1918. His publications of series of woodcuts followed one another at a rapid pace and secured him international fame. Among his works from this period, we can cite 25 images of the passion of a man (la passion d’un homme) (1918), My book of hours (Mon livre d’heures) (1919), The Sun (Le Soleil) (1919), Idée. His birth, his life, his death (Sa naissance, sa vie, sa mort) (1920), Histoire sans paroles (1920) or La Ville, started in 1918 and completed in 1925. At that time, he also made illustrations for works by Thomas Mann, Émile Zola or Stefan Zweig.

In 1919, the First World War ended recently, he saw the beginning of the period known as the Roaring Twenties. It is characterized by its effervescence, its cultural ferment and a return to the taste of life and pleasures after four years of war; it influences the artist who launches, in addition to his graphic work, in painting and watercolor. That year, he founded Éditions du Sablier with the novelist and poet René Arcos. It is also exhibited at the Kundig Library in Geneva. In 1921, My Book of Hours enjoyed a popular edition thanks to the Munich publisher Kurt Wolff and was printed in 15,000 copies in three years.

Never the less, Masereel could not return to Belgium at the end of World War I because, being a pacifist, he was considered refusing to serve in the Belgian army. Nonetheless, when a circle of friends in Antwerp interested in art and literature decided to found the magazine Lumière, Masereel was one of the artists invited to illustrate the text and the column headings. The magazine was first published in Antwerp in August 1919. It was an artistic and literary journal published in French. The magazine’s title Lumière was a reference to the French magazine Clarté, which was published in Paris by Henri Barbusse. The principal artists who illustrated the text and the column headings in addition to Masereel himself were Jan Frans Cantré, Jozef Cantré, Henri van Straten, and Joris Minne. Together, they became known as ‘De Vijf’ or ‘Les Cinq’ (‘The Five’). Lumière was a key force in generating renewed interest in wood engraving in Belgium. The five artists in the ‘De Vijf’ group were instrumental in popularizing the art of wood, copper and linoleum engraving and introducing Expressionism in early 20th-century Belgium.

In 1921 Masereel leaves Geneva and returned to Paris, where he painted his famous street scenes, the Montmartre paintings.

He is exhibited at the Parisian gallery Nouvel Essor. He also undertakes a trip to Berlin with Carl and Thea Sternheim, a couple of German literati fervent admirers of his work; Carl is a writer and Masereel illustrates one of his short stories, Fairfax, in 1922. In Berlin, Masereel notably meets the painter George Grosz with whom he becomes friends.

Until 1925, Masereel exhibited in Paris and in Germany, and his first monograph, written by Stefan Zweig and Arthur Holitscher, was published there in 1923. In 1925, La Ville was finally published and the money he earned in illustrating Charles De Coster’s Ulenspiegel allows him to leave Paris to live in a fisherman’s house in Equihen near Boulogne-sur-Mer. He painted coastal areas, ports, and portraits of sailors and fishermen. He continues to be exhibited in Paris and Germany.

In 1926, he received a little recognition from his native country through an individual exhibition of his paintings and watercolors at the Le Centaure gallery in Brussels. In 1929, the Belgian authorities issued him his passport.

During the 1930s, he produced fewer illustrations and engravings but continued to paint and exhibit. His pacifist commitment did not falter; he took part in the World Congress against War and Fascism in Amsterdam in 1932 as a co-organizer for Belgium and continued to collaborate on anti-fascist monthly and weekly newspapers. His work is internationally known, pirate editions of his picture novels were even published in China and when he visited Russia in 1935, the reception was warm.

His work is widely known and disseminated in Germany and when the Nazis came to power in 1933, his picture-novels and illustrated books were massively confiscated and destroyed: his “social-humanitarian-pacifist” commitment was of course little appreciated by the government and the National Socialist regime. It was a week before Hitler’s election that he lost sight of Gorge Grosz, who fled to the United States. In 1938, his paintings were taken from the walls of German museums. However, they will neither be sold nor destroyed. Shortly before the start of the Second World War, Masereel continued to create and he was a drawing teacher for the workers of the Painting Circle of the Union of Syndicates of the Paris Region. He even tried to enlist in the French army but was refused because of his age. In mid-June 1940, he took the road to the exodus and left Paris with his wife to go to Avignon via Bordeaux and Bellac. He even tries to flee to South America by contacting Louis Aragon and Elsa Triolet, but his project fails.

During the Occupation, Masereel did everything to avoid the Nazis and he left Avignon in 1943 to take refuge in Monflanquin in Lot-et-Garonne and then moved to Claude Sarrau de Boynet’s castle. It was during this period that he met his future second wife, the Avignon artist Laure Malclès (1911-1981). He also loses his friend and master Romain Rolland, who died in 1944.

At the end of World War II, Masereel was able to resume his artistic work and produced woodcuts and paintings.

He was appointed professor at the Hochschule der Bildenden Künste Saar in Saarbrücken from 1947 to 1951 and in 1948, his first exhibition in Germany since the end of the war opened at the Günther gallery in Mannheim. He designed a large mosaic for the facade of the Villeroy & Boch headquarters in Mettlach in 1949.

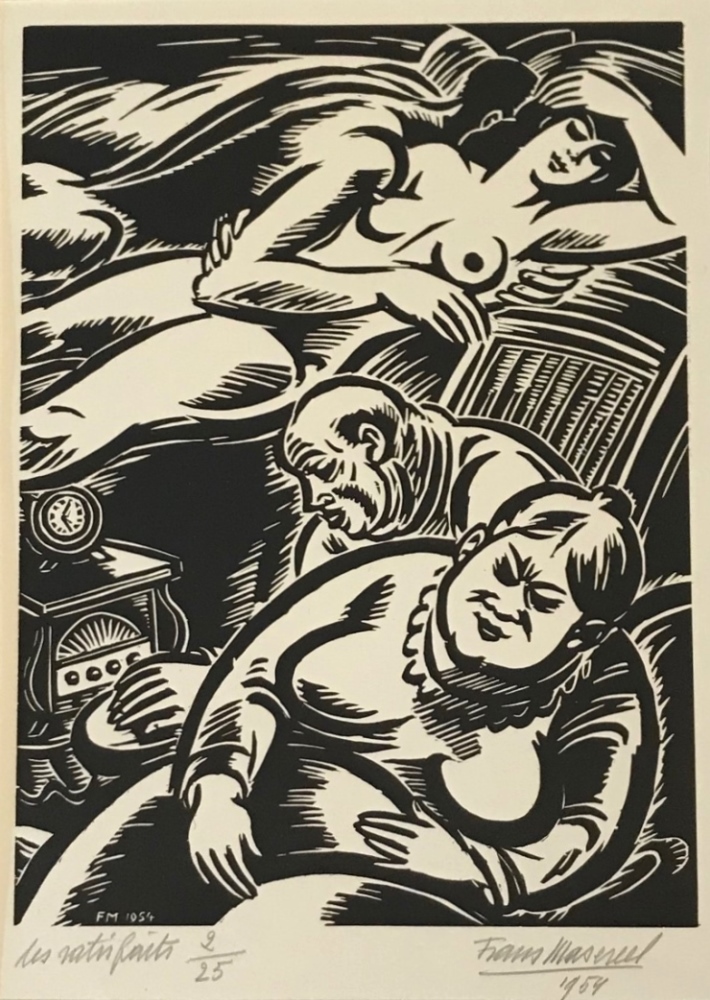

In 1949, Masereel moved to Nice where he lived and worked for twenty years. Until 1968, he created several series of woodcuts which differed from his “novels in pictures” and constituted more variations on the subject than a continuous narrative. He also designed sets and costumes for many theatrical productions, and received the graphic art prize at the Venice Biennale in 1951, then worked and exhibited with Picasso between 1952 and 1954 and completed his consecration in Belgium by being appointed member of the Royal Academy of Sciences, Letters and Fine Arts of Belgium. The artist was honoured in numerous exhibitions and became a member of several academies.

When Pauline died in 1969, Frans Masereel married Laure Malclès and moved to Avignon the same year. He died there on January 3, 1972 and his body was repatriated to Ghent. A large funeral ceremony takes place in his honor in the hall of the Museum of Fine Arts in Ghent. Many Belgian and foreign dignitaries pay him a final tribute and accompany the funeral procession to the Campo Santo cemetery in Mont-Saint-Amand (Sint-Amandsberg). Laure Malclès-Masereel died in 1981.

The artist gave his name to the cultural organization Masereelfonds as was named after him the Frans Masereel Centre studio facility at Kasterlee.

#biography